Why Australia’s 2025 election matters more than it seems

What could the outcome tell us about political trends at home and abroad?

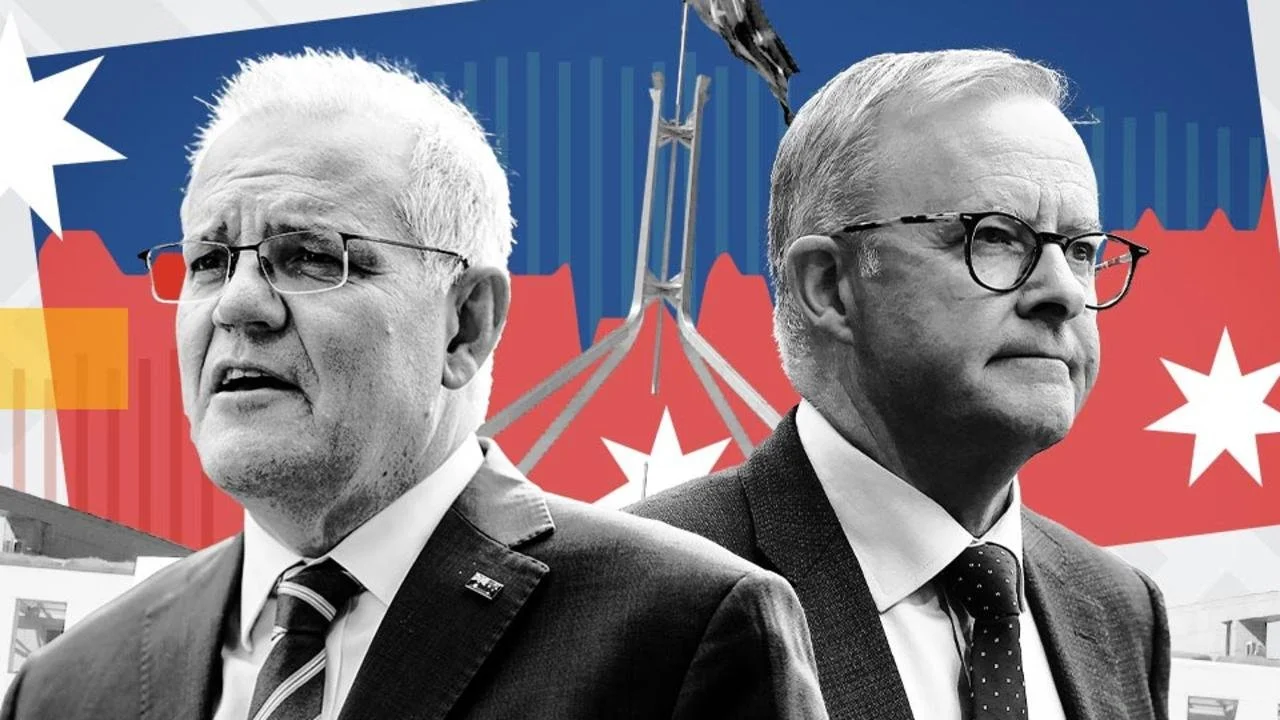

On the 3rd of May, Australians will head to the polls in what could be a pivotal election in the country’s history. Anthony Albanese, the incumbent Prime Minister and leader of the Labor Party, is looking to secure a second term for the centre-left government, however is facing an uphill battle from the centre-right Liberal-National coalition, headed by Peter Dutton. Polling has shown a consistent lead for the coalition, although this has tightened in recent weeks. With Australia playing a vital role position in the increasingly important Pacific, this election could have huge implications for that region, as well as other democracies in the developed world. Therefore, it is worth examining this election, and understanding the possible results.

One of the reasons this election is important is because it could tell us if the trend of voting against the incumbent seen throughout the world in 2024 will continue. Over the past eighteen months, incumbent parties in the UK, the USA, South Africa, India, Germany and many other countries have faced significant losses, even if they still continued to form the government. However, Australia very much has a culture of pro-incumbency. Since 1931, every party has secured a second term (although Gough Whitlam’s two terms in the 1970s were very short), and Prime Ministers such as Robert Menzies, Bob Hawke and John Howard have won many elections themselves. This culture of voting for the incumbent party is why the polling in this election is so significant; it marks a clear shift away from the norms of Australian politics and if it holds then Albanese’s Labor Party will be the first party in nearly a century to not win a second term. If this happens, then it indicates that the global trend of voting against the incumbent is still very much alive and well, and could have potential implications for other elections. However, if Albanese does secure a second term, this might mark the end of this trend we have seen, and might mark a transition to a more stable form of politics in the English-speaking world. Furthermore, if Mark Carney’s Liberal Party win a fourth term in Canada and if Albanese wins five days later, this signals a clear end to this voting trend.

In addition, this election could mark a rightward shift in Australia, consistent with shifts seen around the world. Liberal leader Peter Dutton has moved the party to the right in the last two years, shown through his comments critical of Sudanese immigrants in Melbourne and his partial opposition to policies that combat climate change. This shift has moved the Liberals away from the more traditionally conservative governments of Malcolm Turnbull (a devout republican, and social progressive) and Scott Morrison (more conservative than Turnbull, but less so than Dutton), back to the right. Indeed, Dutton’s political views echo those of former Liberal Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who himself expressed skepticism towards climate change, migration, and supports socially conservative policies such as opposition to euthanasia and abortion. If Dutton wins the election, this could be seen as part of the rightward shift seen recently throughout the world (particularly in Germany and the USA). This shift is not just a shift towards the centre-right, but to a more populist ideology. Therefore, this election could confirm the idea that developed democracies are experiencing a shift towards more conservative, populist governments, which could hold implications for future elections worldwide, truly showing its significance. However, if Albanese holds onto power, it could show that this rightward shift is not occurring everywhere, and in some countries the political centre is holding on. Such a result was seen in the UK last year, and in Western Germany a few months ago. Therefore, the Australian election will serve as a litmus test of whether this increase in support for right-wing populist governments and parties is truly a global phenomenon.

Finally, another consequence of a potential Liberal victory would possibly be the decimation of independents and smaller right-leaning parties. Three years ago, 10 independents were elected to the House of Representatives, mostly in former Liberal seats such as Wentworth and Mackellar. These politicians, so-called ‘teal independents’, tended to win their traditionally conservative seats through their support of policies aimed at mitigating climate change, a more socially progressive outlook and a focus on reducing corruption in federal government. Despite these more left-wing policies, they tend to be seen as to the right of the Labor Party, and ideologically closer to the leftmost faction of the Coalition. These politicians experienced high levels of success at the most recent election due to the Liberal Party suffering heavy defeats, however if the Liberals rebound, as is expected, it is possible they could lose their seats. This phenomenon has happened before; in 2019 Liberal candidate Dave Sharma won back the division of Wentworth from a teal independent, in line with a strong performance for the coalition that year. Therefore, it seems likely that many of these seats will again vote blue. However, Dutton’s shift to the right might dissuade these socially liberal, environmentally-concerned voters. While these mostly suburban seats have previously been associated with traditionally conservative voters, a significant shift left has been observed in recent years. For example, in the 2023 Australian Indigenous Voice referendum, which promised to establish an advisory branch of government specifically concerned with the interests of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, saw nearly all of the seats held by teal independents vote ‘Yes’ (apart from the highly rural Victorian division of Indi), even as the Liberal Party endorsed a ‘no’ vote and 60% of Australians rejected the proposition. The support seen for the Aboriginal Voice in teal independent seats, in contrast with the heavy opposition seen in safe Coalition seats, could indicate that voters in these divisions have moved on from the Liberal Party, suggesting that these teal independents might be here to stay.

As to who will win, the Coalition has a polling lead coming into the election, however Labor has tightened the gap in recent weeks. If this trend continues, then it could be seen that Labor is likely to win a second term. However, it is entirely possible that these polls could be incorrect, as they were in 2019. In that year, Labor had a larger poll lead yet still lost, a factor that Liberal Prime Minister Scott Morrison attributed to the ‘quiet Australians’ who had voted Liberal without publicising it. Indeed, similar phenomena have occurred in other countries such as the USA, and to a lesser extent the UK last year, where polling tends to overestimate the support for left-leaning parties and underestimate the support for right-wing parties. Historically called the ‘shy Tory’ factor in this country, it is therefore entirely possible that there are many ‘shy Liberals’ in Australia who do not want to publicise their support for the increasingly right-wing Liberal Party, and the coalition actually does have more of a lead over Labor. However, the election is guaranteed to be close, and with three weeks until the polls close, it is therefore ultimately unpredictable from this far out.